02 Exploits

Buffer Overflow

A buffer overflow is a bug that occurs when a program writes data outside the bounds of allocated memory. This can be exploited by an attacker to execute arbitrary code or to crash the program. This can be used:

- to access (read only) data on the target

- to manipulate data on the target

- to sabotage a system (political goals, vandalism, extortion, …)

- to steal the identity of the system (and use it for futher attacks like phishing, spam, …)

- to steal resources and use them for malicious purposes (e.g. crypto mining)

Other approaches are: compromise browser, vm, container, … and use them as an execution environment. Network access may be enough to escape the sandbox.

A buffer overflow can not only be used to overwrite variables but also to overwrite the return address of a function. This can be used to execute arbitrary code (return-oriented programming).

Simple Example

In this example, the first argument can be used to overwrite the content of s2.

The required length of the argument depends on the architecture and the compiler.

Create a file buf01.c with the following content and compile it with gcc -o buf01 buf01.c.

#include <string.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void test (int argc, char *argv[]) {

char s2[4] = "yes"; // set s2 to "yes"

char s1[4] = "abc"; // set s1 to "abc"

strcpy(s1, argv[1]); // copy argv[1] into s1

puts(s2); // print s2

}

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

test(argc, argv);

}

Return Address Override

Return addresses can be overwritten using buffer overflows. This will lead to segmentation faults most of the time, because most of the addresses are invalid memory locations.

But if they are overwritten in a targeted manner, they can be used to execute arbitrary code.

- Jump to attack-code in same buffer

- Jump to attack-code in different buffer

- Jump to some system library call

Fuzzing

Fuzzing is a technique to find buffer overflows. Random values are thrown at interfaces to see if they cause a crash or unexpected behavior. This is easy to automate and finds buffer overflows and bad error handling fast.

Countermeasure

- Memory-layout randomization: place stack and heap at random places in memory, so that the attacker does not know where to jump to.

Attacker can use NOP-slider/jump-catcher. This countermeasure only marginally increases difficulty. - NX-Bit (no-execute): mark memory as non-executable, so that the attacker cannot execute code in the stack or heap.

May impact some applications that need to execute code in the stack or heap (e.g. old Adobe Acrobat Reader). Can be circumvented by return-oriented programming.

Error Handling

Error handing can be a vulnerability itself:

- DoS be resource exhaustion (CPU, RAM, I/O)

- data leakage (usernames, account numbers, internal software versions, …)

- hints to buffer overflows

- hints to other vulnerabilities or shoddy coding practices

When handling an error, do not fail too verbose or silent. First contains to much information which can be used by an attacker to exploit a system. Second does not allow a legitimate user to fix the problem.

Bad/Good Practices

Bad

- fail silently

- give too little or too much information

- call debug code in production

- consume a lot of resources

- log more than possible to save (attacker might flood logs)

- have side-effects on other activities

- give misleading information (confuses user, does not deter attacker)

- make it obvious that some errors are not handled

- anything overly complex

Good

- handle all errors

- be fault-tolerant whenever it does not cost you much

- be user-friendly unless that leaks data or can cause DoS

- do not give details that do not refer to the input

- do not echo the input to prevent reflector attacks

- test error code under high error-load

- expect error handling to be abused

- keep it simple

Algorithmic Complexity

Algorithmic complexity attacks are based on the fact that some algorithms have a worst-case complexity that is much higher than the average complexity. This can be used to cause a DoS by feeding the algorithm with data that causes the worst-case complexity.

Examples:

- Quicksort: O(n^2) worst-case, O(n log n) average-case

Worst-case is easy to hit: feed pre-sorted data - Hashtables: O(n) worst-case, O(1) average-case

Worst-case: Feed a lot of data which causes a lot of collisions - Regular expressions: exponential execution time if bad input or bad expression have been provided

Practical Example

What does the error message Segmentation Fault mean?

Segmentation Fault occurs when the software tries to access an invalid memory location.

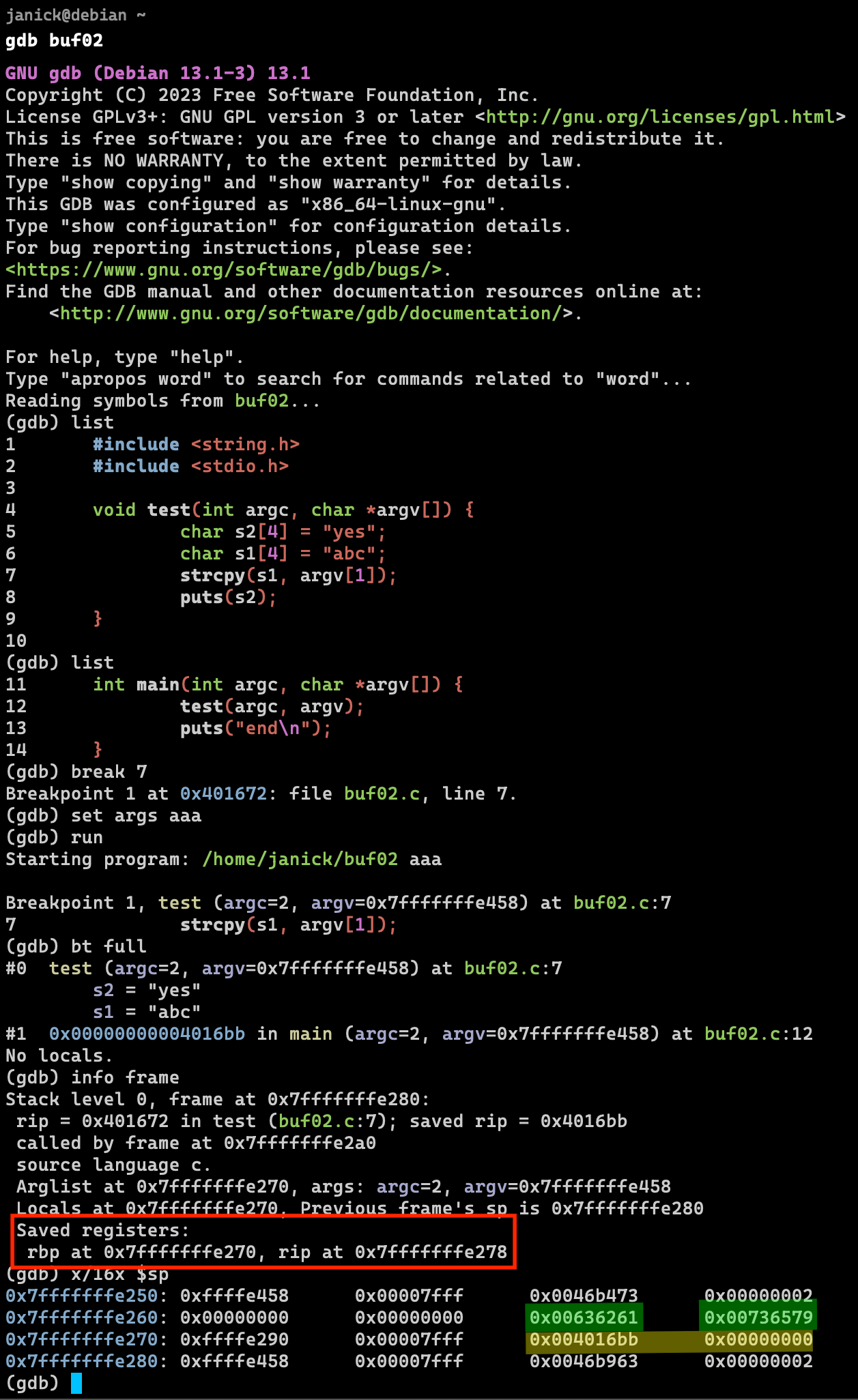

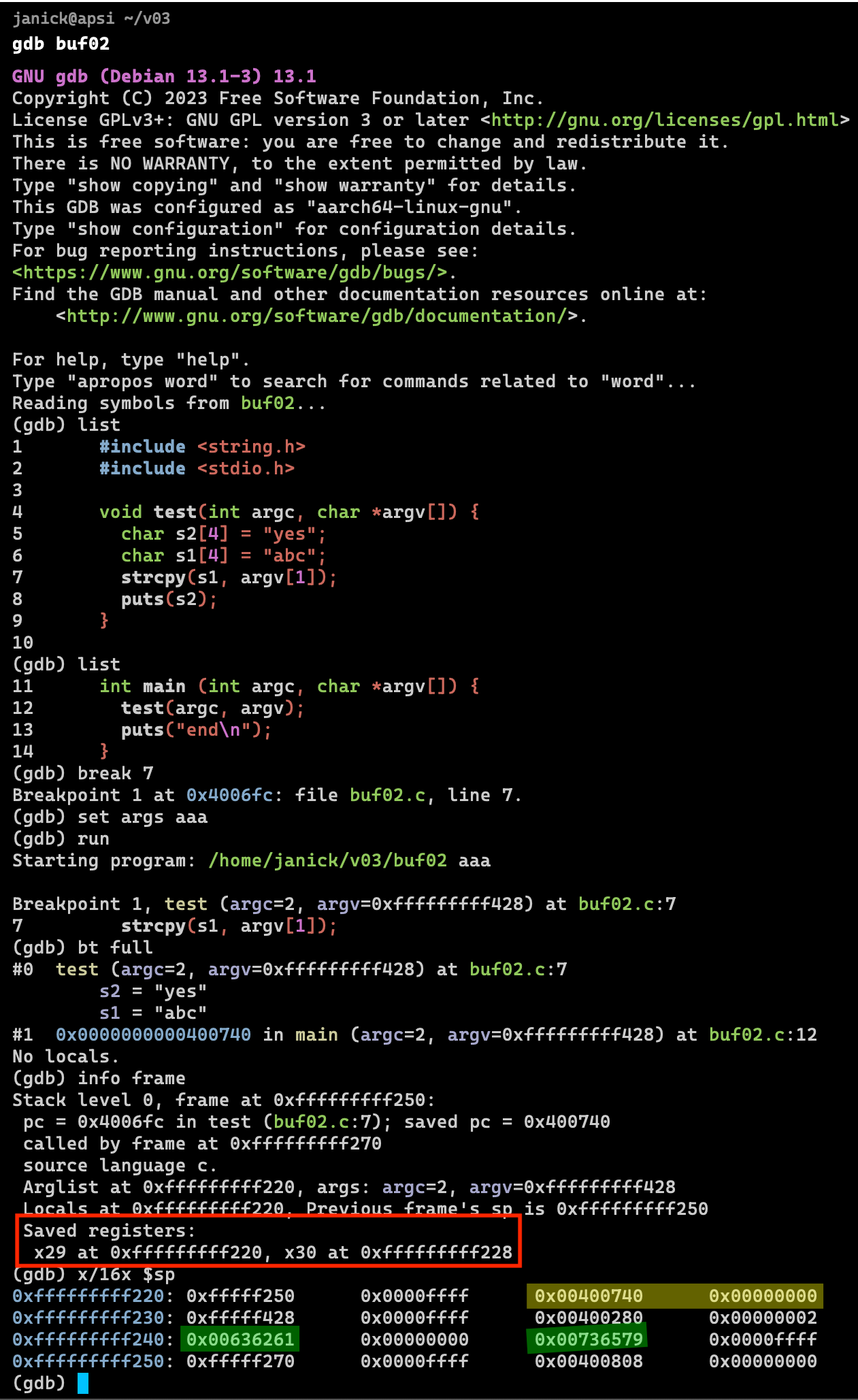

Where are the strings and return address?

The strings and return address are saved on the stack. The exact location can be viewed by debugging the software.

- The variables are located in the stack (green) and contain the values in HEX.

- The RIP (return instruction pointer) is also located int the stack (yellow) and points to

0x00000000004016bb.

The registers have different names on different architectures (e.g. arm or x86).

Where does the segfault occur in the example above?

If the variable s1 overflows, the effect is visible because puts(s2) will print the overflow.

The segfault will occur when the process tries to jump back to an invalid return address.

What is the worst-case time complexity of a hash table?

The worst-case time complexity of a hash table is O(n). This happens if all elements are hashed to the same bucket and all elements need to be searched.

What are characteristics of a good hash function used for hash tables?

The hash function needs to be quick (performant) and evenly distributed to minimize collisions.

Which techniques can be used to handle collisions in hash tables?

- Separate chaining: use a linked list to store all elements that hash to the same bucket

- Open addressing: use the next free bucket to store the element that hashes to the same bucket

- Double hashing: use a second hash function to find the next free bucket

Why are cryptographic hash functions not suitable for hash tables?

Performance is not good enough.

What are typical use cases for regular expressions?

Input validation or parsing.

What makes a good pattern, what makes a bad one?

A bad regular expression contains groups that can be repeated indefinitely.

What are other attack vectors for highly scalable cloud systems?

Cloud-computing environments bill by the amount of resources used. A competitor could use bad regex expressions to keep systems busy and increase costs.

Does this regular expression work for email validation?

^([a-zA-Z0-9])(([\-.]|[_]+)?([a-zA-Z0-9]))*(@){1}[a-z0-9]+[.]{1}(([a-z]{2,3})|([a-z]{2,3}[.]{1}[a-z]{2,3}))$

No, it does not work for email validation.

Valid addresses like [email protected] are not accepted.

What is the worst-case complexity? (Use a regex tester like regex101.com)

When using an invalid email address in the form [email protected], steps are doubled for each new x.

What would be a “malicous” input?